Thanks to Day, Mirna, Gita, and Bella for watching and discussing this movie with me.

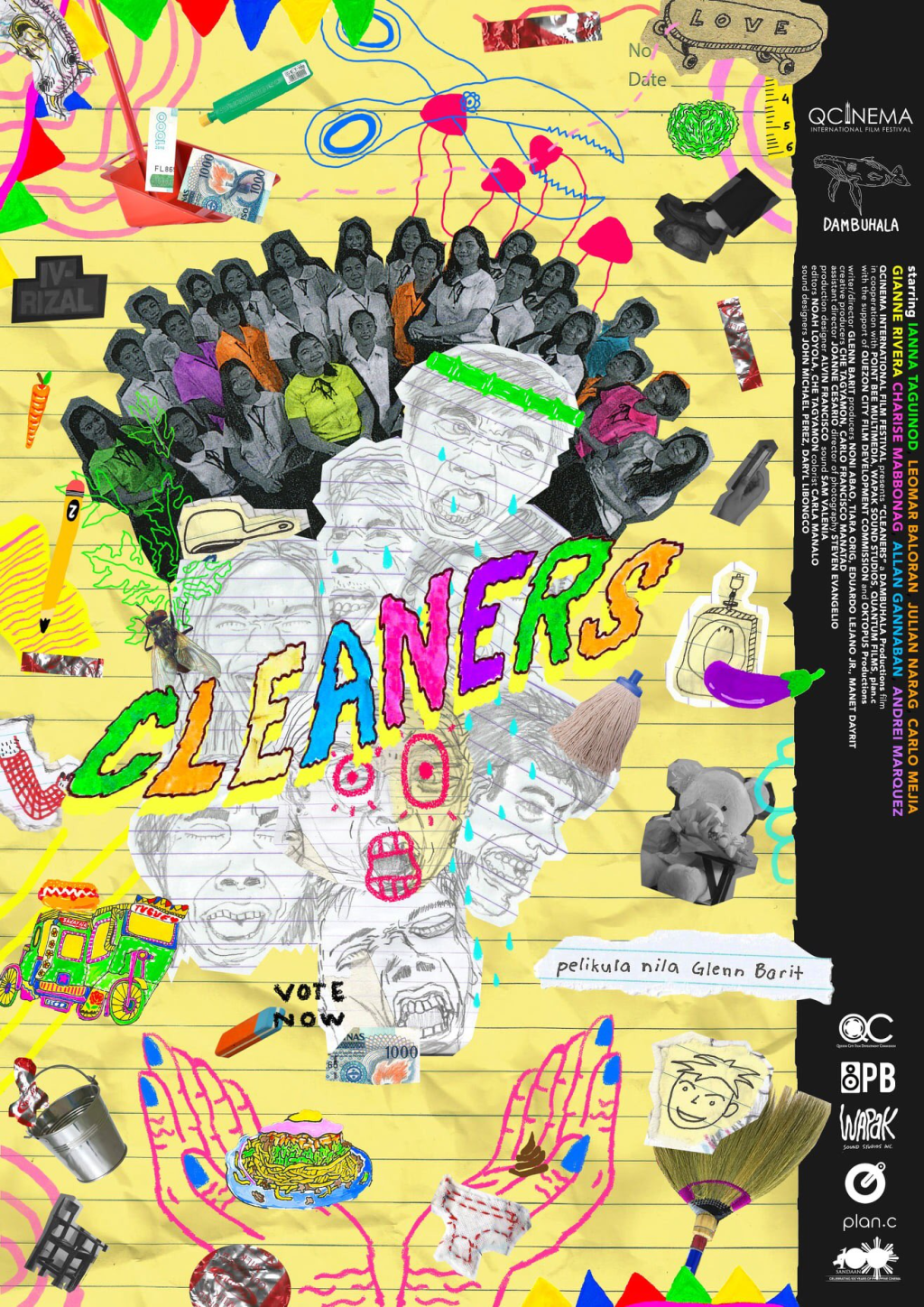

Cleaners (2019), directed by Glenn Barit, tells some slices of everyday life among Filipino high-schoolers in early 2000s. Weaving four separate yet connected mini-stories, the movie offers bitter-sweet, nostalgic youth of friendship and love, with sprinkles of politics, that allows the adults to stay in their jealousy. Each episode is a simple story: a girl who hates dirt but shitting herself in school, emo-rock boys making friend with a nerdy-traditional-music-lover girl, a boy with uncircumcised penis who fell in love with a pregnant-by-accident girl, and a young son of local politicians who got to fix his broken friendship with a punk-ish boy by vandalizing his family’s campaign. But telling these stories through an intricate and laborious production create its own charm. The production team took the scenes, finalized the offline cut of the film, exported it at eight frames per second, then printed each frame out to look like photocopies. Then, for months, they manually highlighted each frame before they batch-scanned and put them back in the original offline cut. (I wish the producer paid the colorist well.)

Grainy black-and-white backgrounds with highlighted colors for each main character makes a simple plot sparkling. Alienated high-schoolers who get to encounter and confront their feelings–positive, negative, something in between–become interesting because they are the multicolor protagonists. From the beginning of the movie, each of these students’ uniforms are already full of color or have their color gradually blooming at the front of the background. This is a way of introducing fragments. As my friend Gita said during our discussion, the film forces us, from the beginning, to focus on their stories. A group of students happen to be in the same classroom and carry the same task for cleaning their space of learning, but each of them has separate stories and urgencies. We don’t get a chance to see them as part of the black and white. Each of them are already different. Colorful. Have I said interesting?

We, the adults, know too well that realities are not black and white. But for Cleaners‘s adolescents, their realities are. Choose one: clean or dirty, good or bad, right or wrong. You can’t be both. So shame out of mistakes is their most fearful feeling and self-interest is their featuring mode. To come-of-age is to be right, to feel righteous, to appear rightful. But once they enter or realize the situations–shitting oneself, encountering unlikely music genre, bad romance involving pregnancy and uncircumcised penis, growing up in a corrupt politicians’ family, they do not get to enjoy the black-and-white. All of mistakes that lead to embarrassing moments turn into a series of awareness that in their youth, life is already difficult. Society is oppressive.

“So, what are they cleaning exactly?” my friend Mirna asked. Some of us (me) tried to answer her question with the most obvious one: their class, their own hygienic compulsion, the messiness of their surroundings–only for them to fail and try again. This answer is uncertain though. At the end of the first half of of the film, we may draw a temporary lesson (if there’s any): dirty is not always bad, dirtiness can be navigated. The first two stories are funny and silly. They invite an impulse to embrace the curse of being dirty and find enclaves of joy. The second half punches down this naivete. The young boy with uncircumcised penis cut his own tip in front of a bully who mocked him and impregnated the girl he likes. Then, the last boy, after witnessing his politicians parents burning down his favorite noodle place for their political interest, sent a bag of money to his punk friend to do an opposition’s job. They could not accept the cleaners in their reality that try to wipe clean their faults through lies and corruption. Politics are dirty. Police are dirty. Don’t you want to clean it? Don’t you want not to join that kind of dirtiness? But dirty politics cannot be overcome with a clean act. One has to play dirty too. “What are they cleaning exactly?” is a twist. These characters cannot pass through the unfinished bridge; they could only sit, hanging their feet, showing what dirty can be.

Wrecking the society that play dirty to the young people is not an option. Yes, these kids rebel. Yes, they run away from night-security and police. Yes, teachers do not understand. Yes, parents are corrupt. Yes, cocky and gossipy peers are the worst. These youngsters live against the norms. They are idealistic, clumsy but heroic. What their bodies do for them–uncontrolled bowel, ovulation, remaining foreskin–cast them away from society; yet, they overcome. They claim back their rights to exist in their shared clean-or-dirty world. Their frustration that stains their uniforms and marks their colorful soul only bursts out loud at the end. They could make a chaos out of the repressive classroom: chairs, tables, boards, chalks, windows, curtains–they deserve to make destruction against the room designed by the corrupted adults. Self-respect, love, and friendship may prevail. But the final scene returns to the clean and neat classroom. Amidst their colors, the society stands.

Cleaners elevate the presentation of simple chronicles. The force of grains and highlighted color pampers our sense of artistic and visual production. We appreciate the hard work, the labor of making art, that telling stories require particular mechanics of asserting textures of images. But the intricacy in production cannot always reach narrative meanings beyond its technical complication. We don’t get a chance to ponder on blank spaces around the characters. Our eyes are too sensitive to spot (high)light that the meanings around the background come up often as a questionable decoration, even though they are the statement of problem that makes possible for the main protagonists to enhance their multicolor. Also, do the colors have their semiotic here? Aren’t a blue uniform for a boy and a pink uniform for a girl he has crushed on too cliché and stereotypical? Each fragment is not particularly consistent with the choice of color; and too bad, their color sticks to them from the beginning to end. They do not change even when their life changes. What is this color then: personality? soul? authenticity? self? Colorful yet static; presumably growing but never mind. They’re still in high-school.

But art does not have to be perfect to make their presence. Cleaners makes many openings about making story through serious thinking on the effects of texture and production. I am charmed by the insistence that elements of contrast can do many many things to simple stories. Barit and the production staffs deserve all the awards the movie has received. Nostalgic as it seems, lives in a contemporary Philippines are both grainy and lively. Come-to-age period might be a simpler time, but it is not at all easy, never pure, always dirty.

you can check the director’s blog here: https://glennbarit.wordpress.com/portfolio/cleaners/