I presented some parts of the essay at the 24th Cornell SEAP Graduate Student Conference (De)Constructing Southeast Asia under the title “Feeling Strange, Feeling Home: An Annotation of Indonesian History.” Along the way, I feel like to stress the subtitle more because it was through bibliographical annotation that I develop my way and form of critique This version is an edited one. I changed some parts of the essay, as I recalled and reflected on my ways of (mis)reading.

This essay weaves words and feelings of reading Indonesian history. It is a reflection and a search: a work in progress of venturing the possibilities of reading as an active mode to enter possible avenues of historiographical knowledge. I learn from Rukiah Kertapati, Qiu Miaojin, Audre Lorde, Dionne Brand, Qwo-Li Driskill, and Marianne Katoppo. They have shown the imaginative labor that challenges the oppression of white heteropatriarchal machines to rebuild the language of the future. In their works, language grounds dreams and vision. Rukiah’s questions burn. Qiu’s sapphic lamentations tear down. Lorde’s poetics open. Brand’s sounds make. Driskill’s words interrogate. Marianne’s stories demand. In Brand’s words, “Here is history too.” Walking with their works, I write this annotation as disruptions to a bibliographical list I use for my comprehension exam. Historians usually use annotated bibliography to provide guidance for other historians and researchers by listing archives, printed materials, locations, people, and numbers of pages. It is a catalog of information, operating as a glimpse into something known and unknown. My annotation is less of guidance and more of an attempt to recognize the stumbles and troubles of reading and writing scholarly works of Indonesia’s history. I want to reimage Indonesia and Southeast Asia at large not only as a place of intellectual inquiry but also as a place of feelings.

1

Robert Elson, The Idea of Indonesia: A History. When the founding parents thought about “Indonesia” in the early twentieth century, arguably, they meant a shared experience and solidarity. Some were thinking through secular-humanistic positions. Some integrated their faith and belief in rooted traditions and religions. They—the intellectuals—were excited. The path of pursuing freedom was in front of their eyes. China and Japan had done it. Pramoedya’s protagonist, Minke, saw it too, that a new, equal society would be a home for Children of All Nations. And yet, here we are. The Raya and Merdeka Merdeka become a memory for many, and for some, it is not so much an experience. When will the scenes from a beautiful life where We feel better. We feel better. Henk Nordholt, Bambang Purwanto, Ratna Saptari (eds.), Perspektif Baru Penulisan Sejarah Indonesia. So, what makes new perspectives, new, when they are always about old experiences and experiences of the old? I truly understand: the book is an invitation for historians of Indonesia to move from “historiografi nasional,” to tell more stories beyond Indonesia’s state project and its bias. But when a white man, a scholar of Indonesia once said to me that Indonesians are apparently bad at writing their own history because of this nationalist bias, I wonder: whose perspectives must be renewed? Jean G. Taylor, Indonesia: Peoples and Histories; Taylor, Global Indonesia. “In an earlier book, Indonesia: Peoples and Histories (Taylor, 2003), I placed Indonesians at the centre of the narrative and attempted to convey the impact of historical events and processes through vignettes of Indonesian lives and stories. Because the theme of this book is the drawing of Indonesia into global history and trends, I necessarily here give far more space to the actions and impact of outsiders.” On page 13, I highlighted this sentence, and scribbled a question: how does putting the word “global” make the book different from the previous one? The regions are never isolated; and since the modern state of Indonesia did not yet exist, not until mid-twentieth century, isn’t the connection between Malay people from Sumatra and Bugis people from Sulawesi already “transnational,” already “global”? I strikethrough the word global.

2

Adrian Lapian, Orang-Laut, Bajak Laut, dan Raja Laut. Adrian knows and argues that a single category of bajak laut (pirate) cannot explain the vast sea of Sulu and the Bajau people. The seas separate and bind islands. Kepulauan. Kelautan. G. J. Knaap, Shallow Waters Rising Tide; Knaap, Heather Sutherland, Monsoon Traders. Wind. Water. Tide. Monsoon season. Ships. Skippers. Commodities. Accountants. Bureaucrats. The harbourmasters’ registers were packed with names and numbers. The Bugis, the Malays, the Dutch, and the Chinese were entangled. Crowd, busy, violent. Leonard Blussé, Bitter Bonds. A woman with a Dutch father and a Japanese mother arrived in Batavia. She was a widow navigating a rigid regulation of property rights. Cornelia van Nijenroode was known in Japan as otemba, the untamable. She was one among the many who shaped the social worlds of the almost modern.

Muridan Widjojo, The Revolt of Prince Nuku. Prince Nuku and his adherents in Tidore, East Seram, and Raja Ampat rebelled against the Dutch East Indies Company. Alliance. Rivalry. Nuku knew he was living in a changing world. He fought both his own Sultanate and its principal rivals. His moves were not self-defeating; he sought help and assistance. The world did not revolve around him. He revolved and made the world. Muridan challenges Leonard Andaya, The World of Maluku, saying that Andaya’s explanation is culturally deterministic and ignores the reasons and interests of every group that supported Nuku. Andaya updates his view. He thinks about ethnic formation rather than the “ethnic” as a rigid category. Leonard Andaya, Leaves of the Same Tree. The fluidity of ethnic identity is a testament to the many ways of navigating the material and spiritual world. Barbara Andaya, To Live as Brothers. And these different ways also clash. The brothers are rivals. The sons move. The family migrates. Perhaps some daughters are left behind. They felt they’d forgotten and moved on. / Their body on the other hand remembered and stayed put. / And so body and soul began to diverge on the sly. //

3

A body remembers itself. Every time they returned to their rented room after nearly twelve hours of working non-stop, their body would demand a bar of white chocolate. / The body wants. The body demands. Why now? Their body never answered … Laurie Sears (ed.). Fantasizing the Feminine. Out of thirteen essays, Ben Anderson’s translation and commentaries of Titie Said’s Bidadari capture me. He titles his article “‘Bullshit!’ S/he Said,” putting a virgule between the third pronouns “she” and “he.” Also, he uses square brackets to separate the Indonesian language and English. “‘dadaku saja yang tetap dada lelaki, tidak berbukit seperti dada Mama. Ah, tapi itu bukan masalah. Toh, gadis-gadis sekarang juga tidak sedikit yang berdada rata. Bahkan para peragawati pun kebanyakan berdada rata’ [‘my breasts were still those of a man not hilly like Mom’s. Ah, but no problem. After all, these days quite a lot of girls are flat-chested. Indeed most models are flat-chested’] (p. 37)” Anderson’s use of punctuation marks is no less important than his translation and commentaries. A reference to one’s body is slashed; language, bracketed. How does punctuation become a vehicle to transcend binary? Or perhaps, they accentuate it? Evelyn Blackwood, Saskia Wieringa (eds.), Female Desires; Tom Boelstroff, Gay Archipelago. “Island of Desires.” “Geographies of Belonging” “But while sex is certainly important to gay and lesbi Indonesians, they consistently valorize same-gender love as more consequential; through it, sex gains meaning and social significance.” Kasih sayang and cinta kasih. A question of nationality and citizenship. Rights to sex. Rights to love. Queer Indonesia Archive. Keeping. Remembering. We are not invisible. We have been here, since always. … their body will understand why they’ve gone through everything that they’ve gone through and all they haven’t gone through and all they’ll never go through—so their body will understand that these feelings are perfectly normal, endured by every soul within every human being.

Economic grievances, millenarian hopes. A prince picked up his sword. Peter Carey, The Power of Prophecy. “‘You alone are the means, / but that not for long, /only to be counted amongst the ancestors. //’ Parangkusuma prophecy, circa 1805.” Dipanegara became a legend, history, and memory. He was (for some, still is) the embodiment of Ratu Adil in the making, meanwhile, people on the ground calculated who was wong islam, who were kapir laknatullah, who were kapir murtad. I listened to Peter Carey’s passionate story of Dipanegara in 2015, during my tenure as an administrative staff in the British Embassy Jakarta. He repeated his words, that “history seems to have little honour in present-day Indonesia.” Babad manuscripts crumble; the shelves, dusty. The result is a historiographical void. I agreed and froze. How to honor history when the New Order government makes my generation hate history (at least the official one)? Also, how to respond to the privilege of a white man in academia who can say to a bunch of “local staff” that we, people living in Indonesia, should honor our own history, our treasure, our pusaka, as if our bodies are not the consequences of history, as if our ordinariness is a sign of ignorance? I walked out quietly. My working hours were over.

My best friend, Perdana Roswaldy, studies plantations. “How Much Land Does a State Need?” they asks, extending Tolstoy’s question. Cornelis Fasseur, The Politics of Colonial Exploitation. Robert Elson, Village Java Under the Cultivation System. The nineteenth-century Cultivation System—cultuurstelsel—in Java was barely a system. The Dutch government had a blueprint on how to extract income from peasants and farmers, but not a systematic strategy on how to enact it. They only had tactics, grounded on the social relations of the local rulers and their subjects. The system was a various set-up of arrangements, a network of everyday relationships on the ground: kinship-in-motion. Jan Breman, Mobilizing Labour for the Global Coffee Market; G. R. Knight, Commodities and Colonialism. Even a not-so-systematic arrangement brought huge profits. Coffee and sugar—they enriched a small European country. Javanese peasants fed the global market. Sartono Kartodirjo, Protest Movements in Rural Java. Peasants rebelled. Plantations are green but they are not forests. Let’s make them red.

4

They were tinkering with solidarity. Takashi Shiraishi, An Age in Motion. Kemajuan. Progress. Pergerakan. Movement. In a new direction in the age of capital, in the age of electric trams, time and space contracted. First, the educated Javanese moved upward; then, they moved laterally as “natives,” as pribumi. Mas Marco Kartodikromo’s “Sama Rasa dan Sama Rata” calls for solidarity and equality, for brotherhood: “Jalan yang kutuju amat panas / Banyak duri pun anginnya keras / Tali-tali mesti kami tatas / Palang-palang juga kami papas. //” The path they were aiming for is scorching, with thorns, raging winds. They must sever bonds, breaking the bars. Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities. A reader, somewhere in Semarang, imagined a corpse lying on the street as they followed the lines of fiction. They did not see it, but their mind looked beyond, making a representation of a body. Anderson commented that Mas Marco’s young man in the story Semarang Hitam, “belongs to the collective body of readers of Indonesia … Notice that Marco feels no need to specify this community by name: it is already there.” But nothing is already there, there. The “there” is crafted. “There” is a site of practices and relations. The proto-Indonesia is not there. It is made there. Out of grievances.

These grievances appeared as a cry. They also appeared as humor. Tom Hoogervorst, Language Ungoverned. Chinese writers in the 1920s and the 1930s clearly knew how to play around with vernacular Malay. They had fun with words: borrowing, cutting, misspelling words so they could express what they thought and felt about living in colonial Indonesia. Irreverence was “coping mechanisms to manage life’s grievances and as gateways to raise awareness about them.” I saved Hoogervorst’s quotation on page 127:

| Outdated wisdom. Let us listen to uncle A Hong haranguing his child: You dog, shrimp-for-brains, buffalo-head, with your handwriting like duck feet, lazy as the devil, in short, you’re considered the Black Sheep. | Ilmoe lama. Tjoba denger ‘ntjek A Hing maki anaknja: asoe loe, otak oedang, kepala kebo, toelisan tjakar beberk, males seperti setan, ringkesnja dianggep Kambing Item. |

For the Chinese, laughing was a way to deal with a sense of loss. Matthew Cohen, Komedi Stamboel. People gathered to watch komedi stamboel, a popular theater, to be entertained. When the performance lacked humor, they did not appreciate it. Novelty in performance, novelty is performance. Komedie Stamboel was a way to fight the boredom of a colonial world, to be mischievous, to be dangerous. It became a performing stage not only for the troupe but also for the audience. They dressed in manners and drank alcohol. A festive carnival, to get by the dark days. You see, we believe that an individual’s path to happiness / is coextensive with the paths of others. / and is sometimes even at cross-purposes— / like a trawl net.//

5

Revolution demands. George Kahin, Nationalism and Revolution. Benedict Anderson, Java in a Time of Revolution. It demands a reason: colonialism and oppression. It demands a spirit: an ideal of youth lightened by the drum of Japan’s war. It demands fire and embers. Guns and burned. Revolution was supposed to be an answer against the return of the Dutch. John Smail, Bandung in the Early Revolution. Anthony Reid, Blood of the People. William Frederick, Visions and Heats. Audrey Kahin (ed.), Regional Dynamics of Indonesian Revolution. Revolution is anger. Bandung lautan api. Aceh in blood. Republik Maluku Selatan attempted to disengage from the new Indonesian government. The replacement of hierarchies. The collapse of one form of government. Revolutionaries faced a dilemma of breaking down with the past and moving forward. Tan Malaka and his supporters were arrested. He rejected a diplomatic means of dealing with the Dutch.

Now, now, who was the friend? Who was the foe? James Siegel, Fetish, Recognition, and Revolution. The street was a dangerous place, a “danger of discovery.” Were they Dutch allies? Were they Republican? Some people hid grenades in their garage: proof of nationalism. Kwee Thiam Tjing, a Chinese-Indonesian journalist from Malang, witnessed his friend’s death in Mergosono together with dozens of Chinese people inside the same pit. “My eyes at that time, readers, could not see anything because it was pinkish red [blood everywhere].” He was angry with Chinese associations that did not do anything about it. “In the next twenty-four hours, if they ignore my request to put soil on the top of the pit, I will beat all siahwee Tionghoa in Malang completely. I don’t care anymore [with] Ang Hien Hoo, Chung Hua Chung Hui, this Chinese doctor, that Chinese professor.” Violence was graphic and real. Who are you: friend or foe? Friend and foe?

6

Who were the caretakers of the white men? Jean G. Taylor, Social Worlds of Batavia. Nyai mistresses and Eurasian wives. For white traders, voyagers, and colonizers, nyai was mysterious—loyal and wretched; an equivalent of a witch—seductive and destructive. Ann Stoler, Carnal Knowledge. Stoler pays too much attention to the colonial psyche. Walking along the archival grain, she is swept over. Housework and care work done by Javanese, Sundanese, and Chinese servants were not necessarily an instrument to foster white bourgeois space, but an everyday form of navigating a space for themselves. Also, intimacy is not an always-present, universal unit as Stoler assumed when she tried to invite a figure of her white mother to engage with Bu Darmo, one of the Javanese domestic workers she interviewed, which ended up with Bu Darmo’s brush-off. Bu Darmo’s reluctance to engage with whiteness is not to charm scholars like Stoler. It is her way of nurturing life. She and many people of her time have survived violence. They have walked out from the archives of history as survivors and become makers of their own world. Reggie Baay, Nyai dan Pergundikan di Hindia Belanda. I say and echo their names. Lamira. Djelema or Oma Pet. Saila. Goei La Nijo Tan. Gouw Pe Nio. Katijem. Tjoe Tanah. Djoemiha. Entjih. Marie or Olus. Srie. Sarina. Minah. Sina. Roebiam. Maria Aprilia. Soeboer. Women of color stay through the everyday.

The everyday unfolds into a particular form of oppression. Saya Shiraishi, Young Heroes. Saya Shiraishi’s book talks about children of my age, the school children sitting in the late New Order classroom. What she writes about school songs, assigned seating, a teacher reading out our names, ini ibu budi, comes to me as a memory of fun and cry of repeating what teachers say and write, rarely (if not never) about “the New Order.” But that is her main point: New Order classrooms have order, and this order emerges from an act of reproducing an authoritative voice. The classroom is family. The classroom is a neighborhood. Jan Newberry, Backdoor Java. My partner’s house in Ambarawa has front and back doors. The back door is connected to a kitchen where I usually pour hot water to brew a cup of coffee. I instantly waved to a neighbor I knew who walked in passing and suddenly turned her head, seeing me standing in the kitchen. She stopped and greeted me; I smiled. “Kampung as Structure of Feeling” is what Newberry explores. “[T]he consciousness of kampung life cannot be reduced to fixed forms.” Kampung are lived, actively, in real relationships—a stage where popular politics and state control meet. … feelings are such a labyrinth! Something is happening in between my quick hand wave and the neighbor’s friendly greeting.

7

Here we are in the garden again. Rudolf Mrázek, A Certain Age. “The houses, roof and everything, were made of bamboo,” Mr. Hardjo said to Mrazék, “All that was above and all that was below was made of bamboo thatching, or of leaves and grass. Yet when it rained, the houses did not leak.” For Mr. Hardjo and his contemporaries, Jakarta was a city of house roofs, walls, windows, fences, and neighborhood streets. Mrazék aims at the memories and experiences of middle-class intellectuals living in Jakarta during the late colonial period. His arrangement of their childhood stories builds one thoughtful remark about “an affinity among the houses, the bodies, hands, faces, and eyes of those who recall them – nostalgia, but also the acts of architecture.” A house, through its dwellers’ eyes and memories, is a site of bodily experiences. Bamboo frames turned into brick walls; unseparated spaces became rooms with functions—remembering these changes means recalling the experience of modernity. “Everywhere at that time, the ‘time of progress’ flowed through the houses and stiffened them up.” A home in the city is an interior place to sense a moment of change.

Nostalgia. Rob Nieuwenhuys, Komen en blijven: Tempo doeloe, een verzonken wereld . Coming and going: a remembrance of the “normal age.” A colonial nostalgia appears in photographs of the tropical garden, the city and village view, the scenery of hills and mountains, the brown coolie and servants. The lives of the cities, tempo doeloe, back in the days. Freek Colombijn, Joost Coté. Cars, Conduits, and Kampongs. The towns transformed. Streets wailed. Buildings howled. To plan is to modernize. Develop! Build! Hygiene! Housing Act. Bandung Plan. Bekasi Project.

Ahh,

Subuh jalan-jalan di kota

tanpa peta, asing juga –

nama-nama-jalan telah diganti, sampai

kehabisan pahlawan mati

jalan dan lorong, jalur-jalur kota

seperti pesan dan janji-janji

yang tidak terpenuhi, torehan di hati –

jalur-jalur kota dipeta tua

berwarna coklat sepia.

Toeti Heraty, “Jogging in Jakarta” (1981).

And love blooms in the shadows of Jakarta. On a Pair of Young Men in the Underground Car Park at FX Sudirman Mall. The two young men even wondered sometimes / why they were the ones who had to show love / can bloom anywhere, even in the dark, / and that love growing in the dark is no less life-giving. //

8

Words and deeds are inseparable. Jane Drakard, A Kingdom of Words. In one of the chapters, Drakard lists the various forms of Malay letters from Minangkabau realm in Sumatra, including their surat cap (seal letter), and goes on to tell readers about the use of writing as a medium for the transmission of power in Malay societies. M. C. Ricklefs, The Seen and Unseen Worlds in Java explains the worlds of power in Java inscribed on the magic books. The Magic Books of Ratu Pakubuwana grounded supernatural power. … asru tobate kang tulis … mighty is the repentance of who write … Letters andl books manifest power that continues and discontinues the ruled subjects as the past, as the future—they can terminate. A white man plays around with this aesthetic of power. Clifford Geertz, Negara is a theatrical manuscript, a play of experiment. Experiment here means a grandeur generalization (or in my view, “too thick” description I can no longer see whether he still describes Balinese politics. He quotes T. S. Eliot’s “still point of the turning” in explaining Balinese polity. What does it even mean?) Benedict Anderson and Merle Ricklefs express their annoyance. The book “suffers from a florid, mannered prose that too often calls attention to the author rather than to its subjects,” said Anderson. “The first victim of the author’s stylish homicide is historical method,” Ricklefs adds. Historical method is the first victim of Geertz’s writing style but not the main one. The Balinese past is.

Writing and translating are acts of reading. Nancy Florida, Writing the Past, Inscribing the Future. Translation is an interplay of various subjectivities across time, spaces, and languages, producing reverberations of different words and worlds. How do historians reflect their translations? How do they obstruct languages? How do they do history? P. Pospos, Muhammad Radja, Telling Lives Telling History. Pospos recalled his childhood; it is Aku dan Toba. Radja remembered Semasa Kecil di Kampung. Susan Rogers translates both books, offering an Introduction on language, themes, and how Pospos and Radja convey what they thought of becoming modern and Indonesian. When do memories of childhood home are less about tradition/modernity and more about a chronicle of and to belong? How do translations convey such longing? Henk Maier, “Beware and Reflect, Remember and Recollect.” Ingat! “It is only by representing and presenting the past through different forms of repetition that events and ideas are retained.” Language is an act of being, of becoming, of living, of resurrecting. … poetry will save his [their] life. Through bodies and words, we remember, we recollect.

In the end …

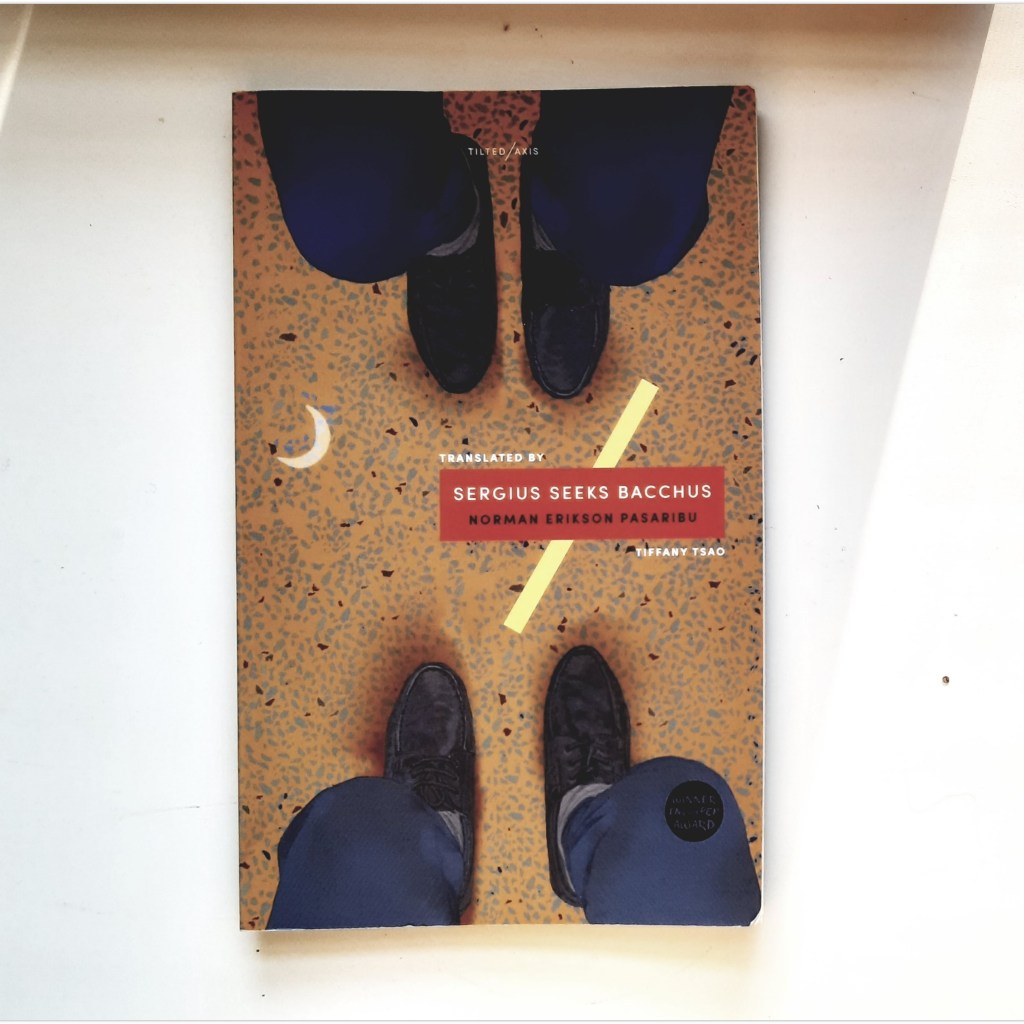

These words can be wrong. They can be true. But I cannot take them back. My iteration cannot be broken. A sense of danger and insecurity lurks behind my back. What I can do is move forward. Norman’s poetry moves me, driving me to write a history I want to read. His poetry-in-translation gives me a clue, that the history-to-come is a mix of the fantastic and the quotidian, the strange and the familiar. … in the end, / there is nothing new under the sun, / Much less under the shade of a tree. Or an armpit. The history-to-come transcends.