10 February 1934. It was a Saturday afternoon, a twelve-year old girl walking on the street of Kepatihan-School, Djember. At the same time a man asked his assistant to put a car on his garage. The assistant did not have a driving license and inexperienced in driving. What he didn’t know: the break apparently wasn’t working. With a full speed, he ran the car, hit the girl and the car fell on the ground. The newspaper did not give us more information about the girl e.g., how critical was her injuries, aside that she was “Arab.” But the man must pay a huge fine and the driver would face trial on the landraad (native court). Three days later, another accident happened. A taxi car from the Pasar street hit the Djompo river wall when it made a turn to the Birnie way. There was no human victim, but the car was completely destroyed. As reported, the steering wheel of the car did not work properly.

We can ask more questions about these two accidents. First, about the people involved. What were their background? What happened to the girl after the accident? What were the reactions of her parents? What happened to the taxi driver? Did he still work as a taxi driver after the incident? What was the decision of the court about the assistant? Did his boss help him? The tricky part is the news didn’t give any name (only initial) and one must search into the government archive to check if this accident is recorded.

Second, about the cars. Aren’t we wondering why the cars in both accidents were not in their best condition? Were they old products? Did the owners not put their car on service? What kind of car did they use, who was the importer? If they were Ford cars, which were popular during the period, how did its auto-service work in Djember in the 1930s? Why the owner and driver did not check their car condition? How much did the cost of auto-service? Was it expensive? Was there any guidance on driving safety? How we understand both accidents, for it was not only about the man behind the wheel, but the wheel itself?

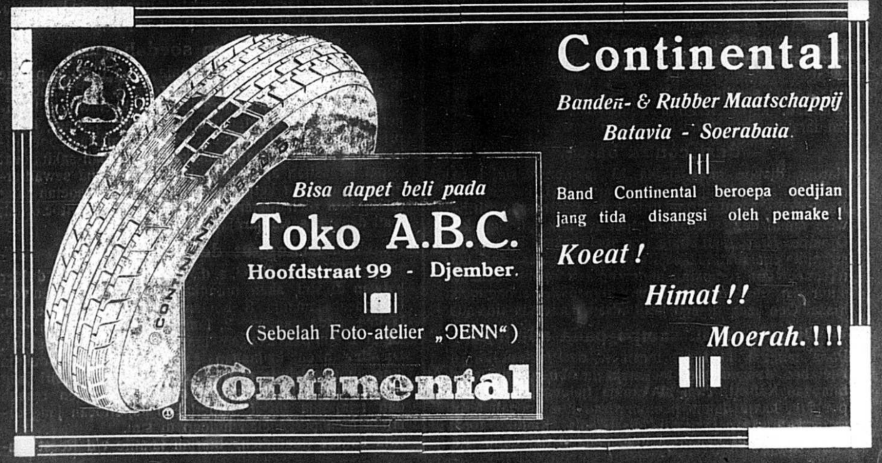

I’ve been attracted to the everyday lives since idkgodknowswhen. When I’m reading old newspapers, I often stop to read some random local news, either accidents, murders, petty crimes, or dispute between neighbors or family members. Sometimes they were funny, mostly tragic. I also like to collect advertisements, reading their copywritings and the illustrations, sometimes looking up the address of a shop. Gazing this mundane past life might be boring for some people, but it gives me an ambiguous feeling. Many news and pictures resemble the present day but they were already behind us. I’m not reading exotic manuscripts or doing palaeography, or dealing with ancient structure of a society; I’m reading something that is not too strange but still unfamiliar.

I used to dismiss this random interest because I don’t know what to make out of it. My academic background always pushes me to think big and abstract. But the more I delve more into the details of history, the more I appreciate the slice-of-life and the quotidian. I gradually understand that the small events appeared in the newspapers have their own life time; they are locked in specific place and time. You can collect them all and make a quantitative record to see a pattern, but if you zoom in each case, the texture is already different.

The illusion of grandeur make this texture dissolve in the big dune of history. A historian, on his Foreword to my friend’s book about a socialist youth organization, praises the book for not only doing a microhistory of family but discussing a bigger topic on pemuda and revolusi. My eyes squinted, and I quickly opened the last part of the book where the story of my friend’s grandma appeared. That is the best part of the book, and I wonder why the topic of revolusi became less important when it’s told from the microstory of a grandma, a family?

Perhaps I’m writing this out of frustration toward modern and contemporary Indonesian history. Not that I claim that there is no scholarly work of history about the social and everyday lives of the people. The great work by an anthropologist Mary Steedly, Rifle Reports, for instance, tells a story of Indonesian independence from the family memory of Batak Karo women and men. I merely wonder why some Indonesian historians (mostly men) still ngotot and tarik urat about kebangsaan, for example, using heroic figures and narrative? We circle around the epic narrative of chivalrous individuals (who contributed to what in nation-state building) or debating again and again about “Indonesian-centric historiography” with few aspiration to see from different angles even though new sources are available. If history is not only a chronological, episodic narrative but also a reconfiguration within a society, then our reconfiguration is like an endless loop, tiresome and tedious.

Are we not curious about what happened in the corner of the city when Sukarno declared independence? Were there any road accidents, or someone stole a handful of rice in the markets? It was still morning anyway, and not everyone knew that Sukarno would make an important speech. What about prostitutions who heard kemerdekaan, were they independent too, as women? What about children without parents, were they excited? How about people outside Java who heard the proclamation not exactly on the same day? I don’t know. Have we ever asked the questions and find the answers?