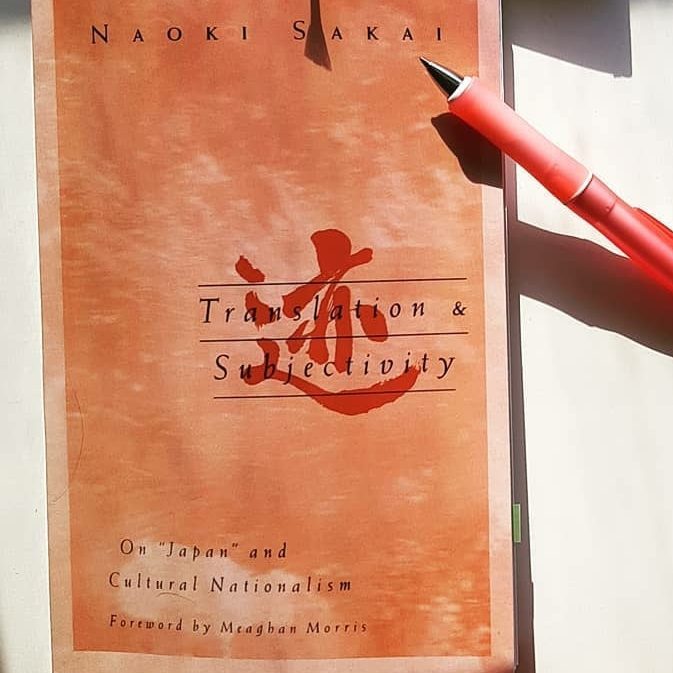

What is translation? What happens in an effort of translation? These are the main questions Naoki Sakai answers in his book Translation and Subjectivity: On “Japan” and Cultural Nationalism (1997). His dense argument covers the limits of construing language as unity or objects of disciplines imbued with nationalist fervor. Through a practical approach, he treats translation as “a social relation, a practice always in some way carried out in the company of others and structuring the situation in which it is performed.” He exposes what he calls the representation of translation, a mode that puts translators as heroic figures who transfer some message from “this” side to “that” side, who becomes the mediator of dialogue between one person or group and another. For Sakai, this mode enables the representation of ethnic or national subjects constitutive to the construction and institutionalization of “national language” or “national literature” (e.g., Japanese kokubungaku 国文学) that assume a sort of “unity.”

After the introductory chapter, the next chapters are a series of his essays that expands his theoretical puzzlement. First, he discussed Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictée (1982) concerning the notion of foreign languages. Next, he exposes the problems of “Japanese” thought, as well as Japanese “thought,” as unavoidable consequences of the comparative mode of history and languages (my fav chapter). Then Sakai examines Watsuji Tetsurō’s reading of Heidegger and his exegesis of “subject.” In the last three essays on this book, Sakai discusses issue of self and cultural difference, the problem of universalism and particularism (hello, modernity), and language in postwar Japan. Taken together, these six essays offer a set of views to see language and translation process as a practice of co(n)figuration: “a practice producing difference out of incommensurability (rather than equivalence out of difference).”

For the purpose of my reading, I highlight two parts of his argument about language and “Japanese thought”: the schema of cofiguration and the regime of translation. The former relates to the “imaginary” feature of the comparative framework between the “West” and the “non-West” (Japan). The juxtaposition (if not oppositional) between the Japanese/English language, for instance, is figurative–sensible and practical to “evoke one to act toward the future on the other.” In working with the schema of cofiguration, Sakai rgues about the regime of translation: “an ideology that makes translators imagine their relationship to what they do in translation as the symmetrical exchange between two languages.” Sakai already works out some parts of such an idea in his previous book Voices of the Past: The Status of Language in Eighteenth-Century Japanese Discourse (1992). But in this book, he accentuates the regime of translation by problematizing the “desire of identity,” which is, for Sakai, emblematic in the fields of history of “Japanese thought.”

As I’m reading this book, my mind often refers back to Benedict Anderson’s The Spectre of Comparisons (1998) that also brings forward the mode of comparison as an operating machine of nationalism in Southeast Asia. Sakai’s essays in this book had appeared in English and Japanese language in the late 1980s and early 1990s, a period when scholarly literature on nationalism was flourishing. Although Sakai and Anderson reach different purposes and arguments, they delve into the politics of cultural nationalism. While Anderson argues about the logic of serial imaginings through multiple forms of technology (prints, census, maps), Sakai emphasizes its operating enunciation. For me, Sakai offers a compelling way to recognize certain practices of translation that carry ideological presumptions. I am tempted to call Sakai’s explanation by appropriating Anderson’s noun: the specter of translation (which makes me sound like an impostor brat).

As a theoretical-driven book, Translation and Subjectivity helps me thinking about the stake of translations and “equivalent seeking” in global intellectual history. If we agree with Sakai that in every communication, failure is always inevitable, the question then is no longer about what was lost in translation (some parts of utterances have already been lost) and the consequences of this loss. Rather, it asks what is happening in the practice of translation? What kind of enunciating practices, including its presumptive dispositions, make it possible for words to “have” equivalence?

Last words: for me, this book is demanding. It is not an easy read, as it requires me to focus on Sakai’s layering sentences and argument sequences. I have many moments when I must repeat a whole paragraph as I cannot grasp his flow. Nonetheless, I find clarity in Sakai’s overall argument. He always provides engaging and compelling questions about his puzzlement, and in many parts, he is completely blunt and straightforward, especially when it comes to the politics of his discipline—comparative literature and Asian studies.