This review is part of the Cat Series.

When the life goes with the common, somehow idle, everydayness, how do we respond to a quiet, uninvited guest? The question is mundane but when you think of it, a guest is like a “disruption” for your day-to-day activities. You would stop doing whatever things you’re doing; you would pause for a while, to greet the guest, whether you want them or not. Your loneliness is interrupted. But for now, the guest is not your fellow human, but a cat.

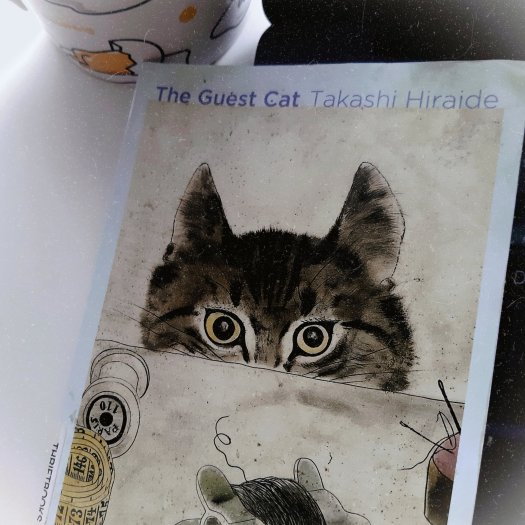

This book tells a quiet story of a relationship between a marriage couple who enjoyed their cottage in the 1980s Tokyo with a cat. This couple worked as freelance editores, and both of them are not fancy with noise or pet. One day a cat invited herself into their small kitchen. They noticed that the cat was barely making sound, so they were fine with her. When a bunch of kids called the cat Chibi, they started to call her with that name too. The story moves forward to the gradually lingering relationship between them and Chibi.

Translated by Eric Selland, this novella unfolds a poetic picture of a conspicuous mildness of life, a mild wish of belonging. Can the cat be ours, but she’s not? Can we be hers, although we’re not? Hiraide is undoubtedly a skillful writer who eloquently plays with metaphors and nuance making. His story flows rike a calm river, pause for the cat, streaming through the mundane life. And Hiraide’s phrases and precisions bring a gentle panorama for such flow:

“A wire laundry line was awkwardly stretched between nails on the guesthouse and on the bis house for hanging out the wash.” (p. 46)

“There at the boundary of the next door neighbor’s house, we saw Chibi slip through a tear in the wire mesh covering a gap in the wooden fence. As soon as she touched ground she turned her back toward us and circled around toward the southern, outer wall of the guesthouse, traveling through the slender fibers of the wild grass.” (p. 73)

Reading this passage gives me not only a very vivid image of Chibi’s movement, but also her spatial context and attitude to this couple. There are many quotable phrases of contemplation in this novella, but the more I delve into the story, the more I less care about the sayings and conversation. The atmosphere of this book lays in such detail descriptions, and it moves me as a reader to actually be there looking at Chibi and feel her presence. Hiraide makes me “felt enveloped in the thickness of its atmosphere” (p. 49).

I think the most striking part of this novel is the constant feeling of alienation. Chibi came and went away as she wanted but the couple grew attachment. But a distance remains, as when the feeling was strong, the cat was no longer there. After all, Chibi was a guest in the life. Death has to take her back. It feels totally normal for us to think about temporariness, yet to move on is something obscure.

“Odd how you still refer to her as a ‘guest’ despite having become so attached.” (p. 55)

At the front of attachment and affection is a temporary visit. Hiraide gives all kinds of genuine melancholy you can think of: the grief of loss, the “secondary resentment” towards the boundaries between life and death, the mournful life moving on into tomorrow. After all, the goddess of Fortuna, of fate, is also unkind. Unkind yet sincere.

I really enjoy the book, as in the end, it gives a dim of light, a sound of meow that is comforting. “There it lay in the darkness–a raw, open space covered by a sheet of pure white” (p. 132). The infinite number of mundanes and the shadow of memories unfold events, open chances, offers hope.